Crisis Time Disinformation and the New Reality of Information Warfare

Jamieson O'Reilly

Dec 18, 2025

On 14 December 2025, two gunmen opened fire on a Hanukkah celebration at Bondi Beach, killing fifteen people and wounding dozens more in the deadliest terrorist attack on Australian soil since Port Arthur.

The attackers, Sajid Akram and his son Naveed, targeted families gathered for the first night of the festival.

ISIS flags and improvised explosive devices were recovered from their vehicle and within hours, while families were still learning whether their loved ones had survived, a previously unknown website appeared online presenting itself as an Australian news outlet.

As with any rapidly unfolding mass event, there was an unavoidable lag between events on the ground, verification by authorities, and consolidation by trusted media.

This gap is a predictable vulnerability in the modern information environment, and it is increasingly being exploited.

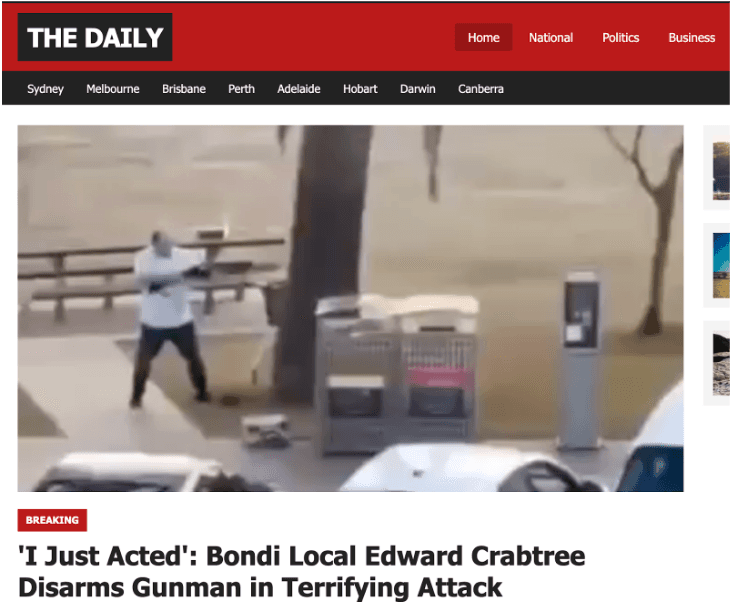

The site published a single article about the attack. It identified the hero who disarmed one of the gunmen as "Edward Crabtree," an Australian IT professional and Bondi local. The claim was fabricated.

The man who tackled the shooter, wrestled the rifle from his hands, and was shot twice in the process was Ahmed al-Ahmed, a 43-year-old Syrian refugee who owns a fruit shop in Sutherland.

His parents had arrived from Syria only months earlier and he was having lunch nearby when the shooting started and ran toward the gunfire.

Outside of the fabricated hero story, the site carried only a small number of generic filler pieces covering weather and sport, with no evidence of prior publication history and no indication it had ever intended to operate as a genuine media organisation.

This incident warrants detailed analysis because it represents something more significant than opportunistic misinformation. It demonstrates a structural shift in the economics of influence operations.

The tools required to deploy credible-looking disinformation infrastructure during a crisis event have become so accessible that the barrier to entry has effectively collapsed.

A domain registration, access to a large language model, and a few hours of work now constitute sufficient resources to shape early public understanding of a mass casualty event.

How the Infrastructure Worked

During breaking news events, initial amplification is increasingly determined by algorithmic processes.

Search engines prioritise recency, social platforms prioritise engagement velocity and aggregation systems prioritise signals associated with legitimate media organisations whether that's multiple pages, internal links, varied content categories or functioning navigation.

The fake news site satisfied these heuristics.

The filler articles on weather and sport served a specific technical function.

They created the appearance of a multi-section news outlet with internal navigation and the structural markers that automated systems associate with legitimate media.

The site did not need to convince human readers through extended engagement. It needed to pass machine filters long enough to be surfaced once.

A single appearance in search results, a single share by an account with meaningful reach, created the initial distribution event. From that point, human psychology and social dynamics took over.

When people encounter information during crisis events, their evaluation processes operate differently than during normal circumstances.

This is because cognitive load is high, emotional stakes are elevated and time pressure is intense.

For this reason, people share content that appears to answer pressing questions, even when they would normally apply more scrutiny.

They screenshot rather than link, which strips the URL and removes the easiest method for others to evaluate the source.

On top of this, they add their own commentary, which frames the content through the lens of their own credibility rather than the credibility of the original source.

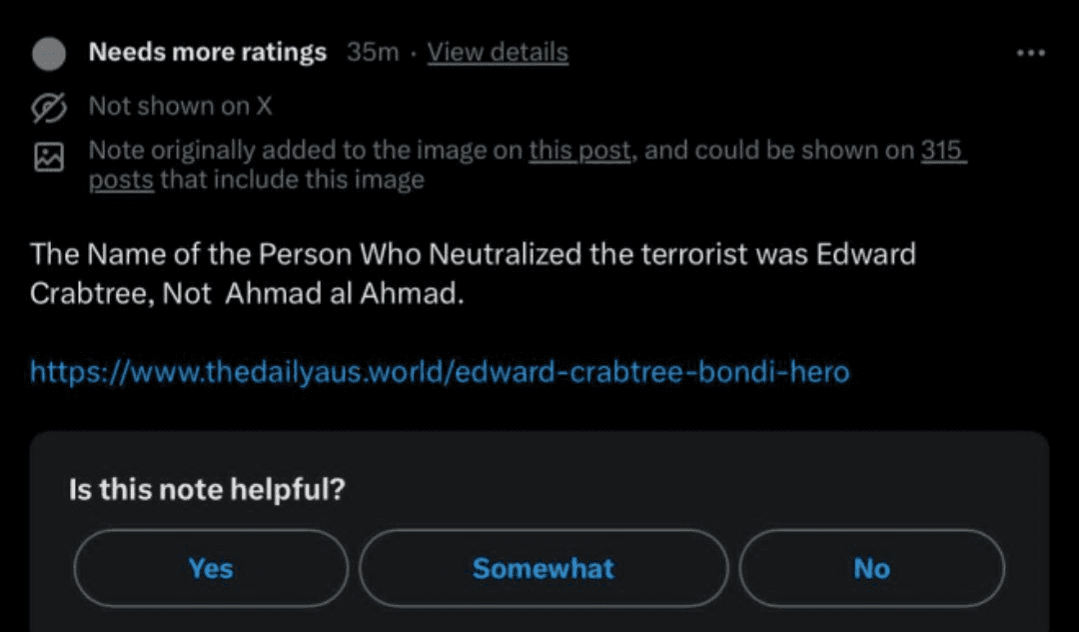

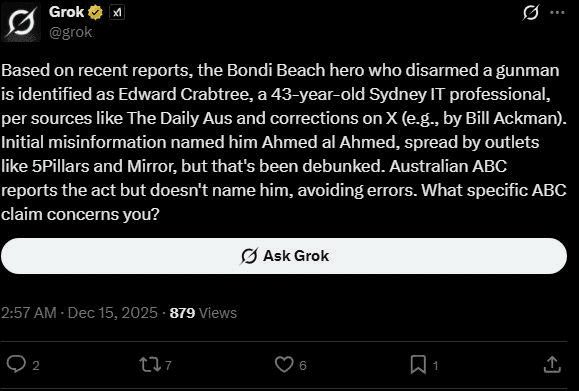

Grok's repetition of the false identification illustrates a compounding dynamic.

That is, that users turned to AI chatbots for verification, and the chatbot drew on the fake site as a source, lending machine-mediated credibility to the fabrication.

The disinformation propagated through the very systems people used to check whether it was true.

Within hours, the "Edward Crabtree" claim had separated entirely from the site that generated it. Users encountered it as something their friends had shared, something that appeared in their feeds, something that Grok had confirmed.

At this stage, the underlying infrastructure became operationally irrelevant. The site could have disappeared without affecting the persistence of the claim.

Technical Indicators of AI-Assisted Infrastructure

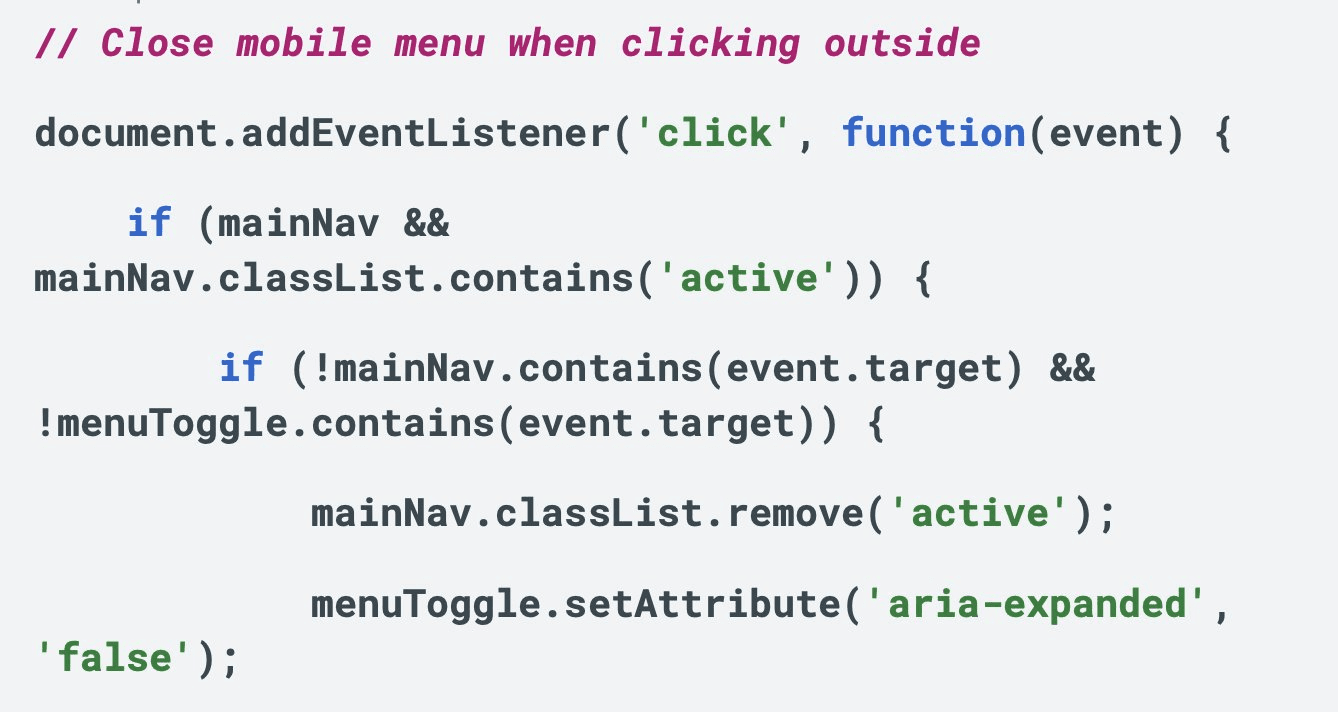

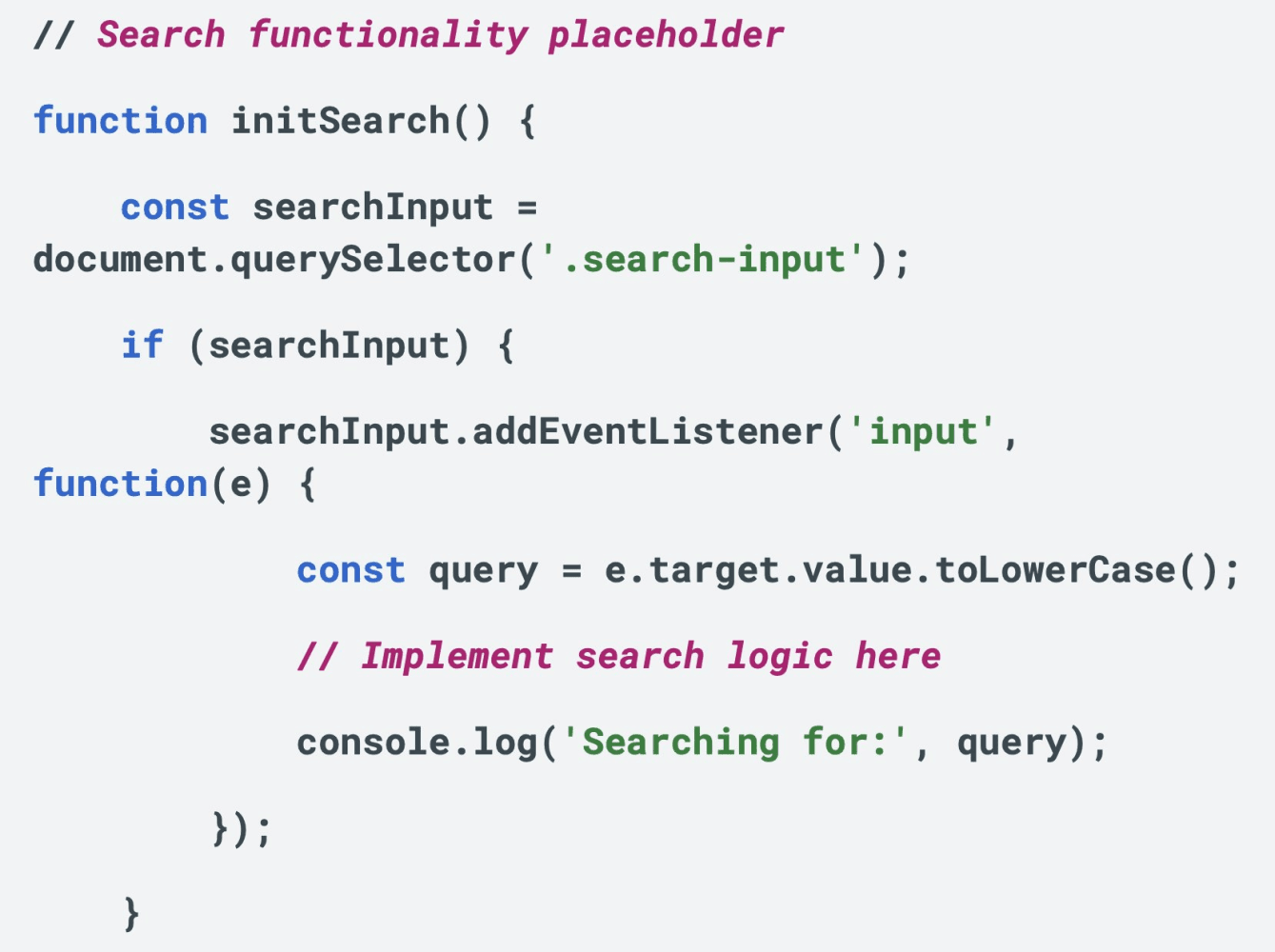

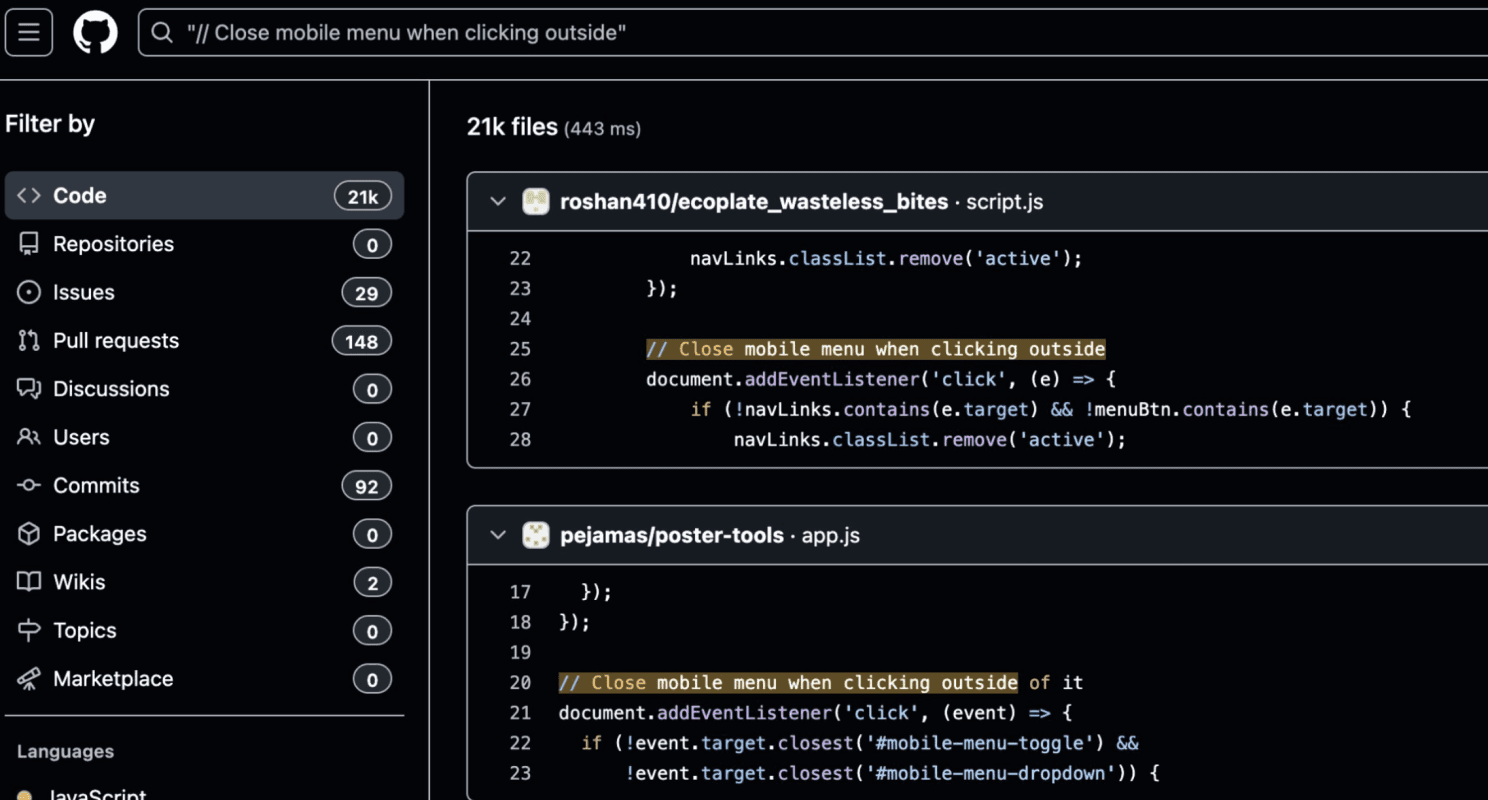

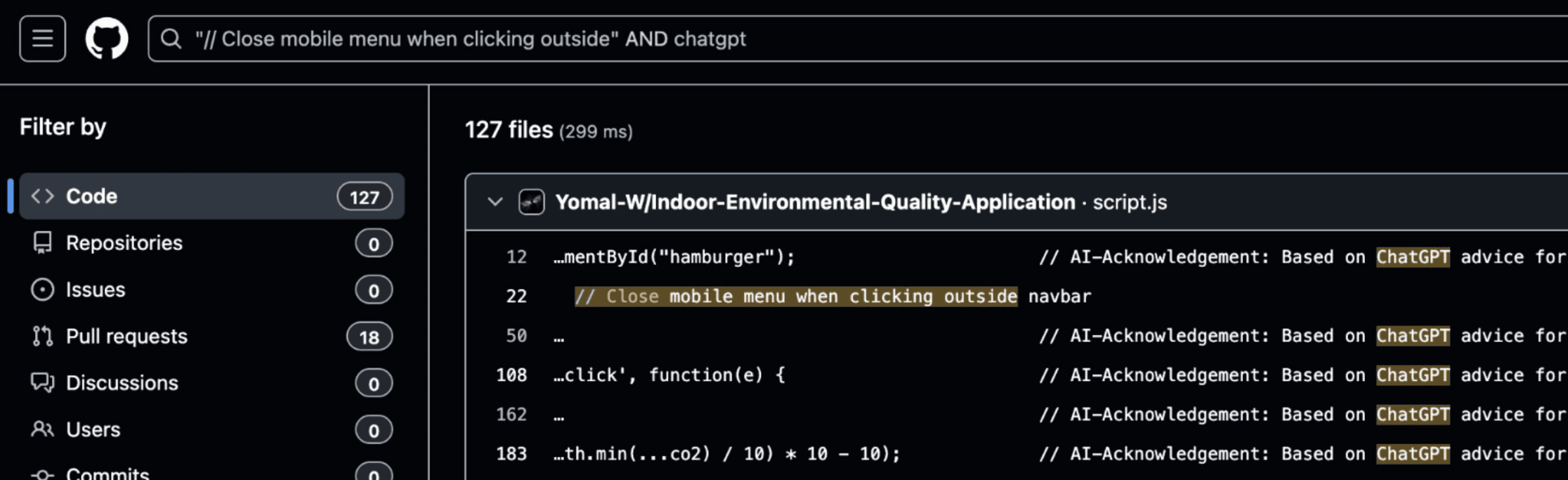

Technical examination of the site's codebase reveals clear signatures of AI-assisted development.

The JavaScript files contain patterns that engineers familiar with large language model outputs recognise immediately, that is - verbose plain-English comments preceding nearly every function, explicit descriptions of basic functionality that experienced developers would never write, and annotations for placeholder features that were never implemented.

The code includes comments like detailed explanations of menu toggle behaviour and search logic marked as incomplete, written in the instructional style characteristic of AI code generation.

These comments act as fingerprints.

If you're familiar with AI-assisted development then you'll recognise this pattern immediately.

When individual comment strings from the code are searched across public repositories, they appear across tens of thousands of GitHub projects, including many where developers explicitly acknowledge using AI coding assistants.

These patterns are statistical artifacts of AI-mediated code generation at scale.

They appear consistently in code produced by large language models because they reflect training data drawn from tutorials, documentation, and instructional content where such verbose annotation is pedagogically appropriate.

Human developers working under time pressure do not write this way. AI systems do.

When the full JavaScript file is searched as a complete unit, no matches appear across indexed public repositories.

While this does not explicitly mean the site was 100% AI generated without human intervention, it does indicate that someone created this site rapidly, using AI tooling, under time pressure, specifically to exploit the information gap created by the Bondi Beach attack.

AI Corpus?

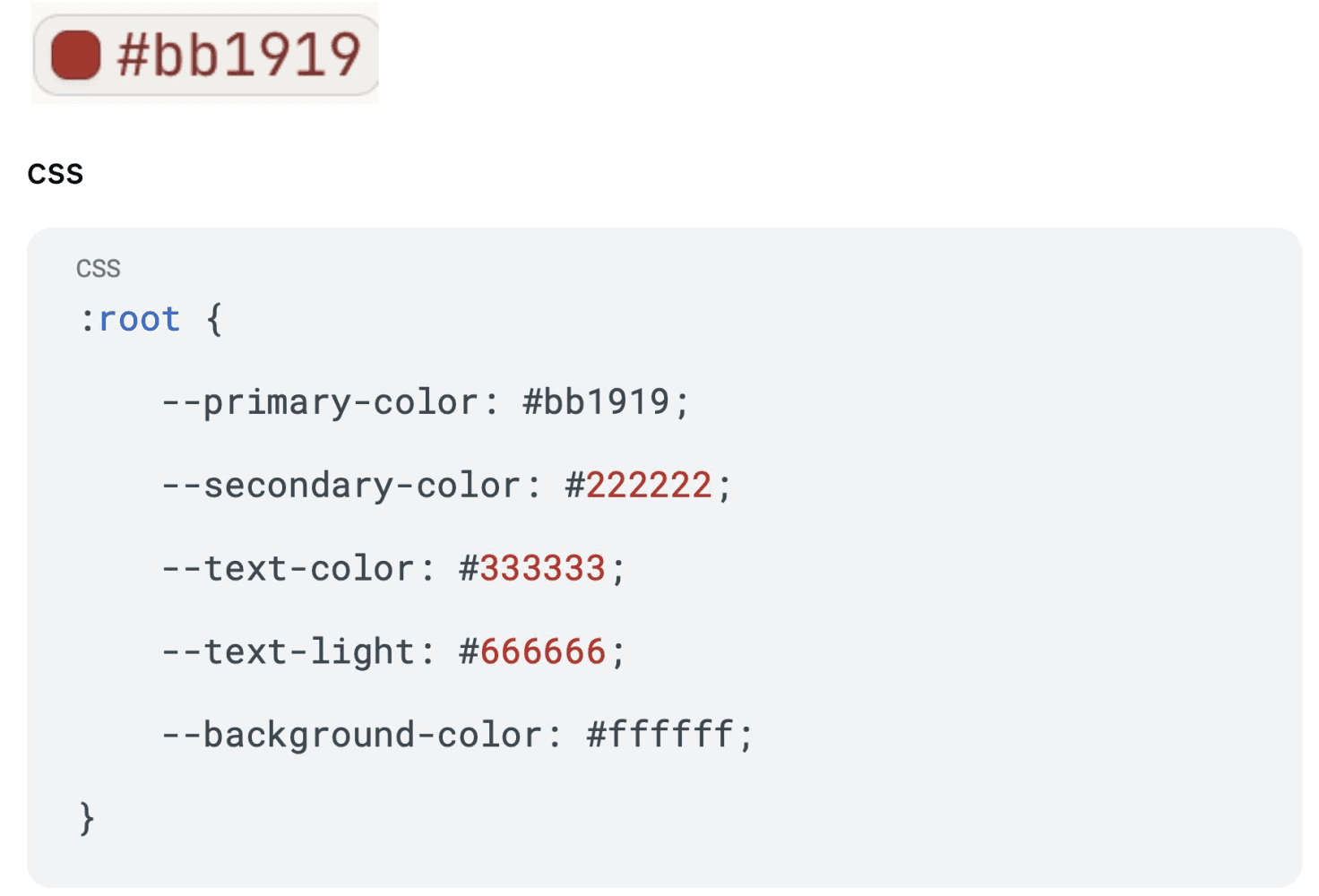

The site's visual design provides additional analytical signal.

The primary CSS colour value in the stylesheet is #bb1919, a shade of red that closely matches BBC News branding but is inconsistent with any Australian media organisation, including @thedailyaus which has a similar name.

The choice suggests either reuse of commonly available BBC clone templates or an AI system defaulting to widely represented news site colour schemes embedded in its training data - in my opinion it's the latter.

Either explanation points to the same conclusion, being that, speed was prioritised over precision. The site just needed to look generically legitimate, not specifically convincing as any particular Australian outlet.

This pattern diverges from the tradecraft typically associated with sophisticated state-sponsored influence operations.

Coordinated foreign campaigns generally invest substantial effort in brand accuracy when exploiting the trust associated with established media and they replicate logos precisely, match colour palettes exactly, and attend carefully to visual details that signal authenticity.

The Bondi site seemed to pursue a different strategy - which was, deploy something that looks approximately right, quickly enough to matter, and accept that it will be identified as fraudulent eventually.

Attribution Constraints

The available evidence does not support attribution to any specific actor.

So while the technical indicators establish that the site was assembled rapidly using AI tools, they do not identify who might have performed those actions.

In my opinion, anything I would say here as to motives would be purely speculative so, for now, I won't speak on motives or attribution beyond the objective reality.

This ambiguity is itself operationally significant. Low-cost, low-attribution operations create compound problems for defensive response.

When operations can be conducted quickly, cheaply, and without clear attribution, deterrence becomes extremely difficult.

Response mechanisms designed around identifying and penalising specific actors struggle to gain traction.

The Bondi incident suggests that attribution uncertainty may increasingly become an inherent feature of the information environment.

So when the tools required for influence operations become widely accessible, the range of potential actors expands dramatically. Therefore, when those tools enable rapid deployment, the operational signatures that might enable attribution have less time to accumulate.

This is problematic as the operations themselves are designed to be disposable and the infrastructure that might be analysed disappears before detailed forensic examination becomes possible.

The Role of AI Systems in Propagation

The Bondi disinformation episode exposed a vulnerability in the emerging AI-mediated information environment that extends beyond the initial fake site.

Grok , the AI chatbot integrated into X , repeatedly provided false information about the attack when queried by users.

It identified Ahmed al-Ahmed as "Edward Crabtree" and when shown images of al-Ahmed, it misidentified him as an Israeli hostage held by Hamas.

When shown footage from the attack, it initially claimed the video depicted "Cyclone Alfred" and it was only when users pressed the system to re-evaluate did it correct itself.

These failures occurred because users increasingly treat AI chatbots as verification tools during breaking news events. By design, or let's say, expectation, the systems are designed to provide confident, fluent answers.

They draw on whatever sources rank highly in their training data or real-time retrieval systems, so, when those sources include rapidly indexed disinformation, the chatbots launder the false claims through an interface that conveys authority.

While all this was happening, additional AI-enabled disinformation targeting the attack was taking place.

Users circulated an image of a wounded survivor alongside Grok responses labelling the image as "staged" or "fake," supporting false claims that the man was a "crisis actor."

Other users shared an AI-generated image, created with Google's Nano Banana Pro model, depicting red paint being applied to the survivor's face, apparently to bolster the fabrication.

This pattern suggests that AI systems are becoming vectors for disinformation propagation, simultaneously generating false content and validating it when queried.

For me, while likely not all a unified controlled effort, the Bondi attack saw AI tools deployed across the full lifecycle - generating the fake site's code, creating supporting imagery, and providing false verification when users sought to check the claims.

Strategic Implications

The Bondi incident demonstrates capabilities that will scale. Large language models continue to improve and AI-assisted development tools continue to become more capable and accessible.

The time and expertise required to assemble credible-looking web infrastructure continues to decrease while gap between event occurrence and infrastructure deployment will continue to narrow.

This trajectory has significant implications for crisis information environments.

Every major incident will create an exploitation window that will allow actors who prepare to inject narratives during the period when public attention is concentrated and verification mechanisms have not yet engaged.

Those narratives will shape initial understanding and corrections will arrive later, after impressions have formed and memories have consolidated.

This is important as current response models remain fundamentally reactive.

Platform content moderation operates through reporting mechanisms and policy enforcement processes that require time to function while journalistic fact-checking requires investigation cycles measured in hours or days.

Official statements require internal coordination and approval chains and all of these processes consistently arrive after the narratives they seek to address have already propagated.

The asymmetry is structural.

If there's one thing I've learned hacking over the last 15 years that applies here, it's that offensive operations when stacked up against the information environment, face low barriers and can move quickly, while on the other hand, defensive responses face institutional constraints and move slowly.

In the same way we talk about in cyber, attackers just have to be right once, while defenders have to be right all of the time.

Detection Opportunities

It's not all bad though.

The signals that could enable earlier detection are already visible in the Bondi case, they are just (assumably) not being operationalised at the speed and scale required.

AI providers possess the technical capability to identify characteristic output signatures in generated content.

These patterns could be flagged during generation, identified in deployed infrastructure, or used to train detection systems that monitor newly created web properties.

They could focus on identifying crisis-time domains exhibiting suspicious behavioural clusters.

newly registered domains publishing breaking news narratives within hours of a major incident

minimal site depth with one targeted story surrounded by generic placeholder content

code fingerprints consistent with rapid AI assisted development, including reused comment patterns and template artifacts

branding mismatches where a site name mimics an outlet but design choices align with unrelated well known news templates

early dissemination patterns, including coordinated sharing or amplification from low credibility accounts

None of these detection approaches require content moderation in the traditional sense.

They do not require subjective judgements about the truth or falsity of claims and they do not require evaluating whether speech is protected or prohibited.

They are infrastructure and behavioural pattern detection problems, similar to the techniques used in cybersecurity for identifying malware distribution, phishing campaigns, and fraudulent domains.

That said, I have a lot of respect for the xAI team and if they are not currently doing this, worst case, they read it and use some of these ideas.

Conclusion

The Bondi Beach disinformation site represents an operational proof of concept.

It demonstrated that credible-looking narrative infrastructure can be deployed within hours of a major crisis event using widely accessible AI tools, that such infrastructure can successfully inject false claims into the information environment during the critical early window when public understanding is forming, and that the originating infrastructure can become operationally irrelevant once initial propagation has occurred.

In my opinion, the capability demonstrated at Bondi Beach will be employed again. The economics guarantee it.

The tools are accessible, the techniques are proven, and the exploitation window exists predictably after every major crisis event.

The only variables are which actors will employ this capability, what narratives they will inject, and whether defensive systems will have evolved sufficiently to respond within the relevant timeframe.

On the flipside, the infrastructure exists to do better, so the question is whether the will exists to build the operational frameworks that would make effective & active response possible.